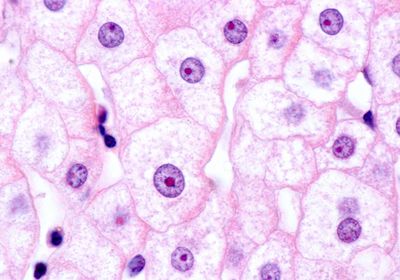

ABOVE: Hepatocytes make a protein that keeps immune cells out of tumors. ©istock, Jose Luis Calvo Martin & Jose Enrique Garcia-Mauriño Muzquiz

When harnessing immune cells to fight cancer, researchers traditionally focused on T cells or natural killer cells circulating through the blood. However, the critical cell types coordinating this immune response may be hidden in unexpected organs. For the past five years, Gregory Beatty, an oncologist at the University of Pennsylvania, has suspected one organ in particular: the liver.

Hepatocytes, the workhorses of the liver, are known for filtering blood toxins and metabolizing nutrients, but they also release proteins that can signal to far-off immune cells. Some of these proteins make up a phenomenon known as the acute phase reaction: a tsunami of inflammatory molecules that course through the bloodstream in the hours after an infection to spur an immune response. Despite this core function of hepatocytes, “most immunologists do not think of the liver,” said Cliona O’Farrelly, a researcher at Trinity College Dublin who has separately studied the role of the liver in immunity.

Evidence suggests that the liver is a potent player in cancer immunology, as liver metastases and high levels of certain liver-related immune proteins reduce patients’ responses to immunotherapy.1,2 In a new study published in Nature Immunology, Beatty and his team further underscored the importance of the liver in anticancer immunity by showing that activation of a specific signaling pathway in hepatocytes reduced T cell infiltration into tumors outside the liver.3 This, in turn, led to worse cancer outcomes. These findings highlight the potential of using the liver to control the immune system’s effective attack on a tumor.

“The liver is a new immune checkpoint for us to think about,” Beatty said. “Finding ways to target that therapeutically holds a lot of promise.”

Beatty’s team previously investigated patterns of immune molecule levels in hepatocytes during cancer, but they still wondered how these liver changes might parallel changes in the tumor itself that have consequences for long-term outcomes.4 For example, tumors with many T cells typically have better outcomes after treatment.5

In the new study, the researchers compared mice with varying numbers of T cells in their pancreatic tumors. They found that the livers of animals with high T cell infiltration in the tumors had lower levels of the immune transcription factor signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT3). Moreover, when they measured the acute phase protein serum amyloid A (SAA) that is typically produced in the liver, its levels were lower in mice with high T cell infiltration. In a previous study, the researchers showed that these molecules promote liver metastases.4

To further elucidate the liver’s role in this immune pathway, the team genetically reduced the production of these molecules specifically in hepatocytes. “Suddenly there were all these T cells in the tumors,” Beatty said. “It was remarkable.” With additional genetic experiments, the team determined that SAA signaled to the toll-like receptor 2 protein on another immune cell type that directs T cells to penetrate the tumors.

Motivated by these findings, Beatty wanted to know whether reduced levels of SAA could drive anticancer responses and survival. He partnered with Vinod Balachandran, an oncologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, to genetically reduce SAA in mice with pancreatic tumors with few T cells. Compared to mice with normal SAA, the genetically modified animals had more T cells in their tumors and longer survival after surgery to remove the tumors. When the team looked at data from 25 people with pancreatic cancer, they found a similar pattern; those who survived longer after surgery had lower SAA levels than those who survived short-term.

“Even though there's huge amounts written about SAA, we really don't actually know what its primary role is,” said O’Farrelly, who was not involved in the study. “For this paper to give a whole other different role to SAA is utterly fascinating.”

Although Beatty focused on pancreatic cancer and melanoma for this work, previous research from his group showed the importance of SAA in lung and colorectal cancers, suggesting that this protein could play a role in many types of cancer.4 Andreas Bergthaler, an immunologist at the Center for Molecular Medicine in Vienna who was not involved in the research, believes that the study adds an important piece to the puzzle of the liver’s immune capabilities. “It's a great example of delineating organ crosstalk,” he said.

However, Bergthaler knows from his own experience linking liver-produced proteins to antiviral T cell responses that it can be hard to nail down the operative proteins among the dozens involved in a given pathway.6 He hopes that future studies will show that interfering with the SAA protein or other elements of the STAT3 pathway slows cancer progression.

Finding these targets is Beatty’s priority. Moreover, he recognizes that other conditions, such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes, can cause liver inflammation, so he hopes to study how those conditions may influence anticancer immunity.

“If we could come up with strategies that intervene in liver inflammation, we could change [the] outcomes for patients that are undergoing surgery,” he said. “That could be a game changer for many patients.”

References

1. Tumeh PC, et al. Liver metastasis and treatment outcome with anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody in patients with melanoma and NSCLC. Cancer Immunol Res. 2017;5(5):417-424.

2. Laino AS, et al. Serum interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein are associated with survival in melanoma patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibition. J Immunother Cancer. 2020;8(1):e000842.

3. Stone ML, et al. Hepatocytes coordinate immune evasion in cancer via release of serum amyloid A proteins. Nat Immunol. 2024;25(5):755-763.

4. Lee JW, et al. Hepatocytes direct the formation of a pro-metastatic niche in the liver. Nature. 2019;567(7747):249-252.

5. Bruni D, et al. The immune contexture and Immunoscore in cancer prognosis and therapeutic efficacy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2020;20(11):662-680.

6. Lercher A, et al. Type I interferon signaling disrupts the hepatic urea cycle and alters systemic metabolism to suppress T cell function. Immunity. 2019;51(6):1074-1087.e9.