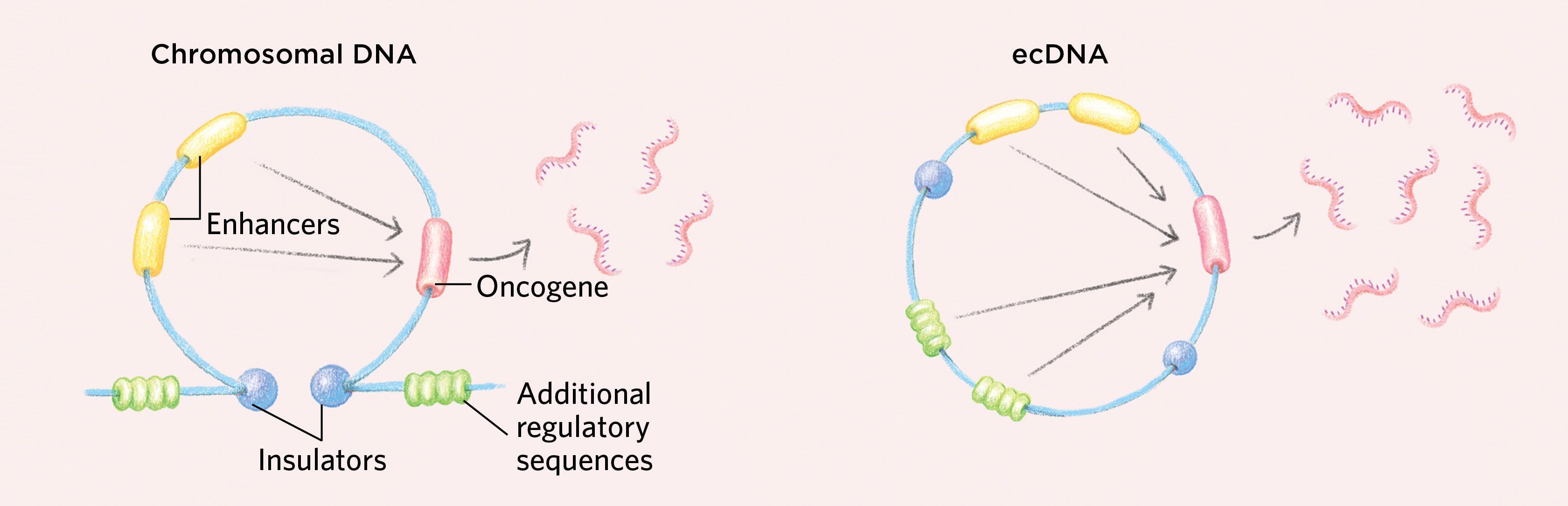

In contrast to chromosomal DNA, which is replicated and divvied up equally among daughter cells during cell division, the extrachromosomal DNA (ecDNA) found in some cancer cells is not always split evenly. Lacking centromeres, these circular bits of DNA are often unevenly parceled to daughter cells. Some daughter cells receive more ecDNA, which they then duplicate, so the copy number of oncogenes in those cells rises quickly. Moreover, because each cell division is essentially a “coin flip” with regard to ecDNA inheritance, variation among the cancerous cell population is preserved, providing an ample supply of the fuel needed for natural selection. These two features in combination could enable cancers containing ecDNA to evolve much more rapidly than cancers lacking ecDNA can.

How ecDNAs Might Support Cancerous Growth

The circular nature of ecDNAs can enable gene interactions that may support the increased transcription of...

Additionally, ecDNAs tend to have a more-open chromatin structure than chromosomes that promotes increased gene expression. DNA is wound around histone cores into units of organization called nucleosomes. On chromosomes, some regions can become highly compacted, rendering the DNA inaccessible to the transcriptional machinery, but ecDNAs have an altered chromatin structure in which the nucleosomes do not compact, resulting in highly accessible DNA that is primed for transcription. Moreover, ecDNAs are loaded with active histone marks but have a paucity of repressive histone marks, promoting high levels of transcription.

Read the full story.

Interested in reading more?